Life in Paris

On July 1, 1867, the British North America Act passed into law creating a new federal system of government in this part of North America. The newly formed federation was named Canada and it consisted of four provinces, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

It is possible that this big change in government meant little to the daily lives of people who lived in the small but thriving town of Paris. After all, the village of Paris had become an incorporated town some 11 years before Confederation.

William Holmes, an Englishman, was the first settler to come to here in 1821. He had a log cabin built in the area that is now the corner of Dumfries and Church Streets. William Curtis and Christopher Holmes (William’s brother) were among other early settlers.

In 1823 Hiram Capron, an ironware salesman from Vermont, came to visit “Squire” William Holmes. He was apparently awed by the beauty and potential of the land that he saw so ideally situated at the forks of the Grand River, because he decided to make it his home. Unlike Holmes, who was mostly interested in building an estate for his family along the lines of the English landed gentry, Capron, later dubbed “King” by his fellow villagers, was interested in bigger things. Writers at the time remember him as a man of “vigour, enterprise and vision”. No surprise then that Capron has been dubbed the founder of Paris. That same year, Capron renounced his American citizenship and took an oath to the British Crown in order to own land in Canada.

Among Capron’s many local achievements, including the building of much of Paris’s early infrastructure, he is credited with naming the town. He chose the name Paris as a nod to the rich gypsum deposits that existed in the area. They were used to make a building material called plaster of Paris. He was also inspired to pay tribute to the illustrious city in France of the same name. But the locals hesitated to have their village identified with a place they associated with bloody revolution, so they initially resisted his choice. Nithsville was one early name given to Paris; it was also called Parisville for a time. Finally, in 1831, the “King” got his way and the village agreed to be known as Paris.

The first locomotive came through town in 1835, opening up the settlement to the wider world.

Master stone mason Levi Boughton moved to town in 1838 and for the next two decades built cobblestone buildings in a style that is unique in Ontario. Most of these beautiful structures are still standing in and around Paris.

In 1850, by the Municipal Act of 1849, Paris was organized as a village. Six years later, in 1856, it was formally incorporated as a town.

Local historian D.A. Smith, in his book “The Forks of the Grand”, writes that early locals were very active participants in self-government. He wrote that Council meetings often went on until the early hours of the morning and were known to be quite raucous at times.

Hugh Finlayson was elected Paris’ first mayor in 1856. The last mayor of Paris was Jack Bawcutt. For in 1998, after 149 years, Paris was amalgamated, losing its formal incorporated status to become one of a number of communities that make up the municipal entity called the County of Brant.

But much happened between the formal beginning and the formal ending of the town of Paris. Just as much happened before it gained formal status, and much has continued to develop, after that status was lost.

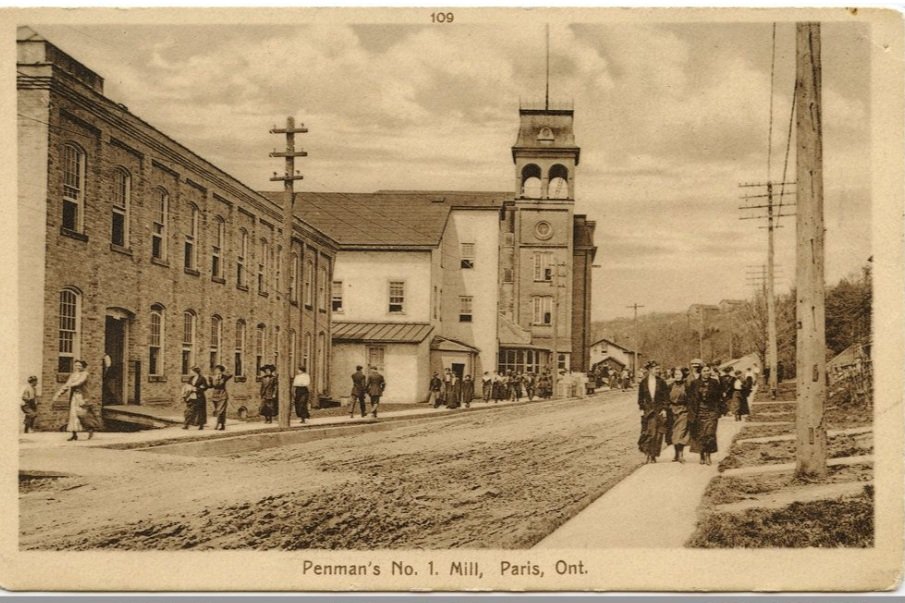

In 1867, the Penman family moved to town and for the next five decades Penmans textile mills defined everyday life in Paris so much so that many townspeople told time by the sound of the Penmans whistle. The company contributed much to the life and welfare of the town, even swelling its population by encouraging skilled textile workers to come from England to work in the mills. Once here, Penmans allowed the immigrants to reimburse the cost of their passage to Canada from their weekly pay packets. The company also built houses for their workers to rent, many of which are still standing today. Willow and West River Streets were the sites of the main mills. Penmans was sold in the 1960s with operations winding down over the next 10 years. Today the only remaining company buildings on West River are condos and apartments.

In 1867 Alexander Graham Bell made his first long distance phone call from Brantford to a shop in downtown Paris. A plaque located in Paris’ downtown marks the spot of this historic event.

The great fire of September 1900 destroyed many of the buildings on Grand River Street and some on the south side of William Street as well. It began in a flour mill and fed by high winds, destroyed 50 shops. After the fire, Paris rebuilt and the ensuing century saw the building of the town’s largest school (Central) and in 1922 the Willett Hospital.

Historical records tell us that Paris has always had a rich social and community life. In the late 1800s May dances and many other cultural events were held in the Old Town Hall. This unique civic hall, still standing in the area known as the Upper Town, is built in the Gothic tradition. Plans are now under way to restore and re-purpose the building for community use. Over the past 160 years the people of Paris have been passionately involved in countless societies, clubs, sporting organizations and many other activities. And that still continues today.

Paris has also experienced more than its share of floods as you might expect in a town where two rivers meet. In some notable years the river has swelled its banks on multiple occasions.

Syl Apps (1915-1998) is known as one of Paris’ most famous sons. Apps was a professional hockey player, an Olympic pole-vaulter and a member of Ontario’s Provincial parliament. But perhaps he is best remembered by his hometown contemporaries for his exemplary and always sportsmanlike behaviour. Apps is recognized on a plaque located in front of the community centre on William Street (originally an arena) that bears his name. The centre is our museum’s home.

Beginning in the twenty first century as a result of provincial growth policies, Paris, as part of the County of Brant, became the focus of intense new development. New houses, increased traffic and a swelling population are now part of the norm.

What would King Capron think if he could once again walk the streets of his town? Would he recognize the same vigour, enterprise and vision that he was known for reflected in the people who live here today?

In 1834, a writer by the name of William Kingston was so charmed by the village that he wrote “Paris is decidedly the prettiest town we have yet seen in Canada”. Many people, locals and visitors alike, would agree with Kingston.

Cate Breaugh,

PMHS Past-President

This story was written to introduce the 2017 PMHS exhibit “Life in Paris”, that celebrated Canada’s 150th birthday.

Sources: At the Forks of the Grand: 20 Historical Essays on Paris, Ontario by Donald A. Smith

The Paris Star Newspaper

PMHS archival records