May the 4th, 2023, Tina was busy setting up the Paris Museum exhibit at Queen's Park! This was a plan long in the works, interrupted by covid, but finally it happened! A team worked together to decide on the content of the case and how it was displayed. The exhibit feature three industries that helped shape Paris; Penmans, Alabastine Co., and Mary Maxim, all industries that had their start in Paris and have grown.

The exhibit will be up in Queen's Park until December.

Our artifacts, Our stories, at Queen’s Park!

Past Exhibits:

Communication

From the beginning of recorded history, humanity has found ingenious ways to communicate over long distances. Our ancestors needed ways to warn their peers of danger, signal friendship, organize military manoeuvres and contact distant kin.

With today's digital phones, online news platforms and social media, the devices used by our ancestors might seem quaint. But as Paris Museum and Historical Society curator Tina Lyon demonstrates in a new exhibit, we are simply using more advanced technology to accomplish the same basic tasks.

The display, entitled "Communication", begins with a military drum. Tina compares it to TikTok which was developed to exchange 15-second bursts of information.

The exhibit next focuses on letters and postcards, which still exist for those who wish to spend $1.07 to use Canada Post. Most Canadians now prefer email, but the purpose is the same.

The third artifact is a 1908 copy of the Paris Transcript, one of eight broadsheet newspapers that served Paris in the early 20th century. Today, most of us read online publications.

Next in the exhibit is a telegraph, developed in the mid-1800s to send vital messages locally and internationally using Morse code over undersea cables and wires strung on poles. The 21st century equivalent, Tina suggests, is Twitter, which allows users to send brief, 140 character messages and rapidly disseminate breaking news.

The fifth artifact in the display is a large wall telephone with a crank. In the mid-1900s people lucky enough to own one of these devices would have to wait until whoever was using the "party line" finished talking. There could be dozens of families sharing the same line, each with an identifiable ring. Nothing stayed private. Certainly, today's cell phones are more portable, convenient and private. But they don't pull communities together the way the old party lines did.

Finally, we come to a beautifully-maintained Remington portable typewriter. Its keyboard is the basis for those we use on our computers. Computers give users access to the Internet, the ability to send instantaneous messages, play interactive games, speed up complex calculations and edit text while writing. But the typewriter still had a few advantages. It was built to last, unlike today's machines with their planned obsolescence. It produced a paper copy without a printer, electricity, cables or ink cartridges. Changing the ribbon was cheap and easy.

Come to the museum and see what our communication artifacts remind you of in today's world. Admire the mechanical prowess of our forbears. Think about the benefits and drawbacks of progress.

Cobblestone Quilt

This quilt featuring some of the Cobblestone Homes in Paris, Ontario was designed and handmade by Linda Charlton and machine quilted by Sarah Yetman.

It has been donated to the Paris Museum for a fund raising event.

Tales of Two Pandemics

History has much to teach us about the COVID-19 pandemic, as our current exhibit at the Paris Museum and Historical Society demonstrates.

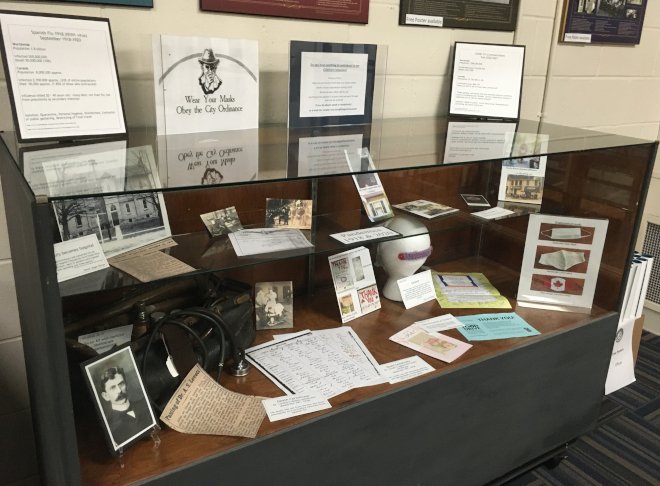

Using artifacts from both the Spanish Flu, which hit Paris on September 27, 1918 and COVID-19, which was confirmed in the County of Brant on March 18, 2020, the exhibit highlights the similarities and differences between the two pandemics.

The list of similarities is long.

In both eras, people wore masks to prevent the disease from spreading. The medical advice was much the same: Cover your mouth and nose, wash your hands regularly and stay home if you have symptoms of the virus. Then as now, schools, churches and cinemas were closed.

During both pandemics, Parisians communicated their concern and sympathy. Our forebears sent hand-written letters. We use email, social media and commercial greeting cards. Like them, we take food to struggling families.

Then, as now, there were front-line heroes. In the 1918 outbreak, a well-liked Paris physician, Dr. Alpheus Lovett worked tirelessly to save lives – but lost his own – to the deadly influenza. The town was grief-stricken. PMHS has his story, his photo, and his obituary on display. Today, we have widened our definition of "hero" to include nurses, personal support workers, therapists and orderlies. Sadly, some have become COVID-19 victims.

But there are differences.

In 1918, the Paris Armoury was converted into a 39-bed emergency hospital. In 2020, extremely ill Parisians were sent Brantford General Hospital. On a per capita basis basis, the Spanish Flu was more lethal. Forty-five Parisians lost their lives, 10 of them aged, 10 of them children. So far, there have been 12 deaths in the area covered by the Brant County Health Unit. The area includes Brantford, Paris, St. George, Burford, Glen Morris and Scotland. We have vaccines, unlike our predecessors. With remarkable speed, 21st century scientists have produced medications to lower the risk and prevent the transmission of the virus.